Why this matters: the FpV hobby went from a grassroots, solder-and-forum craft to a mostly closed, company-controlled experience. That shift happened fast and it rewired who builds the tech.

NickFPV traces the FpV hobby from a garage experiment in 1986 to a market dominated by one firm. The story explains why some pilots resist the convenience of digital systems.

TL;DR

Early FpV grew from tinkers sharing hacks and code. Analog systems forced builders to learn electronics, firmware and antennas. DJI introduced a polished digital video stack that worked out of the box. It boosted adoption and video quality—but it also closed the ecosystem. The result: less DIY innovation, more vendor lock-in.

Origins: Larry, a security camera and the first ‘fly-through’

In 1986 Larry EKG soldered a security camera to an RC plane and watched live video on a TV in a van. The feed was noisy, but it proved the concept. The plane crashed; they rebuilt. By 1989 coloured cameras and stronger transmitters let them fly kilometres with stable video.

Community birth: forums, RC Cam and viral footage

Early attempts didn’t catch on until the internet let tinkerers share designs. Thomas Black (Mr. RC Cam) and small MSN groups iterated camera/transmitter builds. Dennis Gratton added head-tracking. A viral golf-course flight made the FpV hobby visible and ignited new companies.

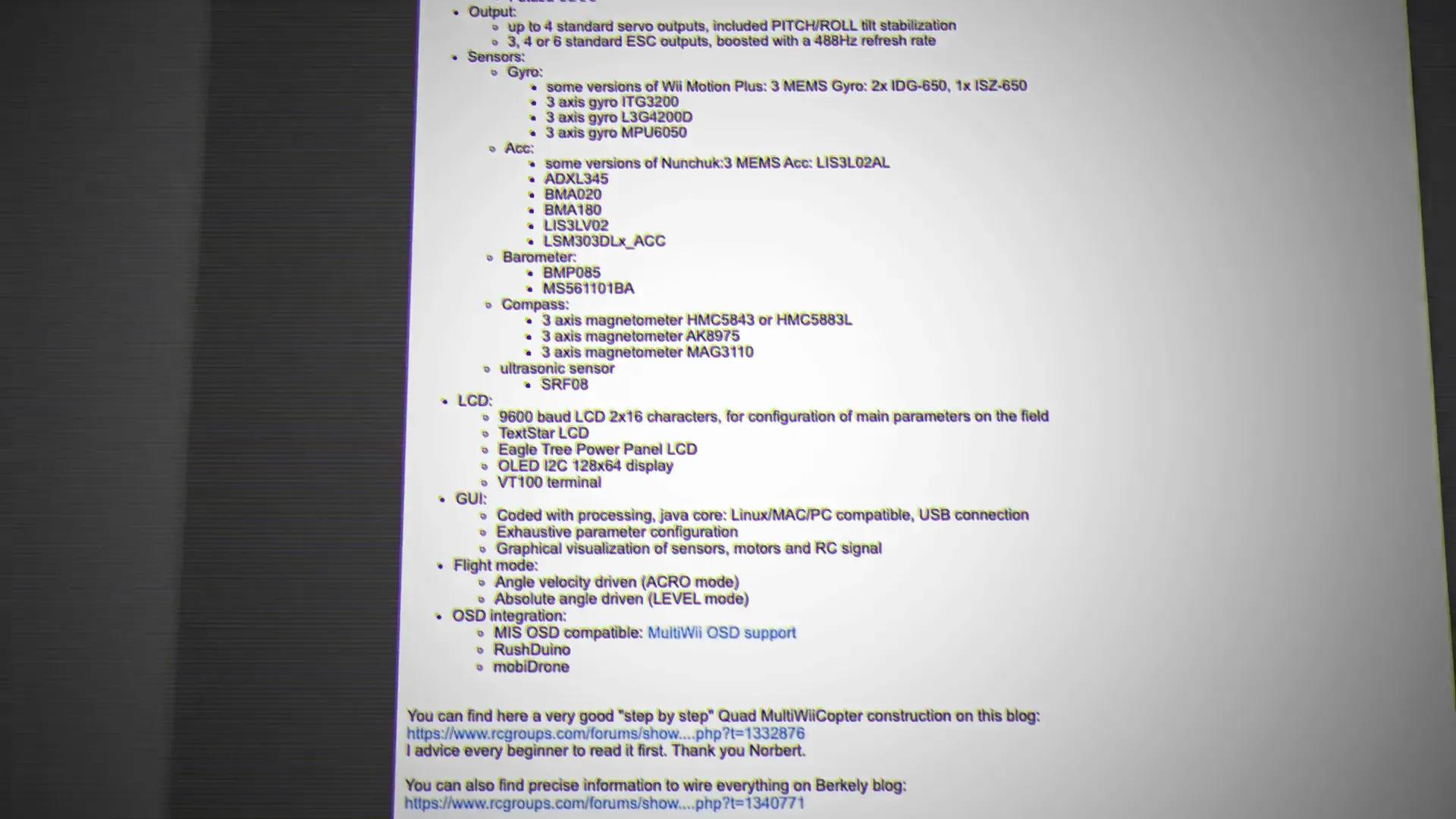

DIY golden era: flight controllers, firmware and open tools

By the late 2000s quadcopters and boards like the KK and MultiWii turned FpV into a builder’s playground. Builders scavenged gyros from Wii remotes, soldered flight controllers, flashed Betaflight and OpenTX, and tuned ESCs. The stack was open and modifiable—innovation came from users.

The analog limit and the accessibility problem

Analog video peaked: it was low-res, glitchy and intimidating for new pilots. The rest of the drone world offered plug-and-play solutions. The FpV hobby had technical depth but lacked broad accessibility. New pilots hit a steep learning curve before even getting useful video.

DJI arrives: digital clarity—plus a closed garden

In 2019 DJI shipped a digital video system that stunned the community. It provided low latency and crisp imagery. It also required DJI cameras, receivers and firmware. The system worked—so pilots bought it. But the parts were proprietary and the stack wasn’t open.

Market consequences: convenience vs control

Sales shifted. Fat Shark and Immersion RC lost ground. DJI expanded with the DJI FPV and Avata and many pilots skipped DIY. YouTube creators preferred the cleaner footage. The FpV hobby split: those who fly closed systems and those who keep building.

Open alternatives appear

Other vendors reacted. HD Zero and WalkSnail offered digital options that aimed to be more modular and community-friendly. They mimic DJI’s image quality or latency but try to remain less locked down. The ecosystem now includes multiple digital systems—but openness varies.

Why the fight matters to builders

The FpV hobby thrived because people fixed, hacked and improved their gear. Closed systems centralise decisions. A vendor can change protocol, disable hardware or price parts arbitrarily. That risk matters if you value repairability and incremental community-driven progress.

Where to from here?

Use the convenience of closed systems—if you want. But keep one foot in the build world. Flash community firmware, test open video stacks and support modular vendors. The FpV hobby stays healthy when builders keep contributing code, hardware and antenna designs.

FAQ

Is DJI illegal or unsafe for hobbyists?

No. DJI gear meets safety standards. The issue is vendor lock-in, not legality. You lose repair and modification freedom when systems close their firmware or hardware interfaces.

Can I mix DJI with my Betaflight builds?

Not easily. DJI’s video links expect compatible receivers and cameras. Flight controllers and autopilot stacks can integrate, but video and VTX remain product-specific unless third-party modules exist.

Which digital system best preserves the DIY ethos?

HD Zero and some WalkSnail implementations lean more modular. They do not match DJI’s polish everywhere, but they keep the door open for community tweaks and third-party modules.

Conclusion

The FpV hobby moved from soldering bench to shop-bought simplicity because one vendor made digital video work and polished it. That improved adoption and footage. It also traded the community’s ability to control the platform. The choice now is practical: buy convenience or support the open stacks that let makers build the next leap.

Takeaways

1) Closed systems sell ease; they erode repair and mod work. Keep a build project.

2) Analog taught pilots systems engineering. Open firmware and modular VTXs preserve that skillset.

3) Support modular vendors or contribute code. The FpV hobby survives on contributors, not only customers.

Credits: original video and research by NickFPV. Sources include CurryKitten’s history, vintage RC Group posts, and creator interviews linked in the video description. Read the original for footage and archive clips.

This article was based from the video How DJI Hijacked FPV